The cyber security market has had its share of dealings with compliance standards and legislation. Some have very broad applicability, others are very narrow, there are mandated and optional ones; technical and managerial; guideline and prescription.

The original version of ISO27001 (BS7799) blazed a trail for the plan-do-check-act management system approach; enshrining the concept of an “Information Security Management System” or “ISMS” into the corporate lexicon; and its adoption and influence has been significant, if not universal.

The modern world however has shifted slightly from an information asset based approach to one that is perhaps more focussed on the threats faced and the defences against these. That is not to say information assets are not important, or that risk assessment isn’t the best way to define control requirements and prioritise investment. It is more that in the modern climate where organised crime, malware as a service and nation state-backed actors are well and truly on the threat radar, there is a need to pre-empt some of the asset classification and risk assessment stages and drop in controls that address the ways in which systems are typically attacked.

Coupled with standards, cyber security teams also have significant amounts of legislation to navigate – these might correspond to certain types of data, certain types of business or certain types of systems.

This blog post doesn’t aim to be definitive or cover everything, more give a brief précis of some of the most interesting current standards and legal/regulatory initiatives that have an effect on cyber security.

Standards in Cyber Security

ISO27001 – The “ISMS” standard

This is nothing if not wide reaching, and with the extended family of standards in the ISO270xx range, is now very comprehensive. The core concept of devising a system for the management of security risks (ISMS) revolves around asset classifications and assessment of threat, vulnerability and impact – hence the process is highly auditable and lends itself to certification. In a nutshell, the controls required are drawn from a library of possible countermeasures, and justified by risk assessment for their applicability.

Certification, the formal assessment of effectiveness, has had variable rates of adoption. Many businesses have aligned to 27001 and adopted its techniques and structures, but nowhere near as many have gone the extra step of getting certified.

The lack of mandation and the perceived overhead of the certification process are often cited as the reasons for this; although one can argue that if the standard has been followed and the systems are in place the hard work is done, and the audit is actually a relevant inexpensive part of the process.

We have blogged extensively about ISMS elements, so follow these links for coverage of here, here, here or here (as examples).

PCI-DSS – The cardholder data standard

PCI DSS has a much narrower scope than ISO27001. It relates to credit card holder data solely, and in fact in systems terms only to those systems on which cardholder data is stored or used.

It is mandated through the card scheme issuers so has some “teeth” but also requires ongoing assessments by certified auditors/advisors; thus there is, in theory, no place to hide. The controls are much more tightly and prescriptively defined so there is less focus on risk assessment to choose controls; rather Visa and MasterCard have defined what risks card holder data is exposed to (or exposes) and laid out the controls they expect to be applied to reduce fraud across the payment community.

There is more information at PCI-DSS and also on our compliance web page.

NCSC Top 10 – The UK government’s advisory standard

A few years back now, the UK government realised that the highly regulated approach to security in the public sector was not replicated across the wider commercial world; and in many business, especially smaller ones, cyber security had relatively low levels of attention.

Hence, in a push to protect businesses and the economy, and reflecting the changes at the time in central government to move away from “prescriptive” approaches to “guidelines” – they issued, along with BIS, a set of ten “Best Practice” or key security controls that should be in place in all businesses, large and small.

These comprise the best combination of management and technical controls; covering prevention, detection and response.

We’ve got a handy reference guide to this standard that provides an excellent starting point for adoption. You can download it here.

Australian ASD Essential Eight – The “lessons learned” standard

If ISO27001 and NCSC Top 10 are high level, this is a geographic low-level equivalent to PCI. Highly specific and well defined, the Australian “ASD Essential Eight” results from research done into the most obvious/critical root causes of many past breaches – in terms of what allowed them to occur or made them as bad as they were – and then listed out the individual controls that address these.

Going beyond just “being helpful” it then became expected and indeed the ‘Top 4’ are required for the largest/main government departments at national/federal level. It is so useful and relevant to today’s threats that there is consideration being given to it being rolled-out across the entirety of the Australian public sector. There are also strong hints that it may then follow into the enterprise space, potentially through supply chain requirements and other national regulations.

Without repeating the contents here (we have blogs on the Essential Eight) it covers controls to reduce the chances of an attack occurring and the degree of damage or impact it can lead to.

Huntsman Security has a compliance report based on the Essential Eight, and has also used it as the underpinnings of its Executive Cyber Scorecard solution for cyber risk measurement and control effectiveness reporting – details here.

C2M2 – Cyber Maturity for Critical Infrastructure

The US Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2) was formulated in the US to help mature cyber security readiness across the energy/electricity industry within the Critical Infrastructure sector.

However, it is useful for any business (regardless of size, type, or industry) to evaluate and improve cybersecurity capabilities. It is also seeing traction outside of the US market in international Critical Infrastructure sectors such as in Australia – see this link.

As with many management systems or maturity based standards it covers the enterprise in a top down manner across 10 domains:

- Risk Management

- Asset, Change, and Configuration Management

- Identity and Access Management

- Threat and Vulnerability Management

- Situational Awareness

- Information Sharing and Communications

- Event and Incident Response, Continuity of Operations

- Supply Chain and External Dependencies Management

- Workforce Management

- Cybersecurity Program Management

It supports the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework and is comprised of three maturity models:

- Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2)

- Electricity Subsector Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (ES-C2M2)

- Oil and Natural Gas Subsector Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (ONG-C2M2)

More details can be found here.

NCSC “Minimum Cyber Security Standard” for UK government

For some time now the UK government approach to security has avoided the definition of hard and fast rules, and opted instead for a “local risk ownership” approach – where business owners or department leads made cyber security risk decisions using National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) guidance.

This approach has shifted slightly and in June 2018 they published a much more prescriptive set of “minimum standards” that should be in place across all government departments.

What isn’t yet as well known (at the time of writing) is how this will be enforced, audited and measured across the UK public sector and its supply chain. However it specifically defines the “shall” things that must be done and “should” things that ought to happen unless there is a good reason.

What is interesting is the degree of overlap with the aforementioned Australian “Essential Eight” standard. See examples in the table below:

| Clause |

Requirement |

| 6.a.ii |

Patching “should” be done (so unless there is a good reason it can’t be) |

| 6.b.ii |

Control software which may access sensitive information |

| 6.b.iii |

Operating systems AND software should be patched regularly |

| 7.a |

Control privileged accounts so they aren’t used for email and web browsing |

| 7.b |

Multi-factor authentication used for administration consoles |

| 10 |

Recover in the event of a failure |

See here for more details, or see our guide to the NCSC 10 Steps.

Cyber security legislation

Standards are undoubtedly a good idea. They have often been devised by practitioners and thought-leaders and hence while they sometimes seem onerous and burdensome, it is rare to find them containing requirements or guidance that aren’t grounded on sound risk principles.

Sometimes, when mandated, they can even have teeth and see widespread adoption.

However, legislation is much more impactful, simply because you have to follow it or risk being fined or sanctioned – plus it has often been devised, at least in part, by regulatory or legislative bodies who have the interests of wider communities at heart.

Often the breadth of scope of legislation is wider than just security – in most of the examples below the sets of rules and implications affect business processes and data more broadly, but have significant security sections, sub-documents or implications.

PSD2 (EBA) – The EU Payment Services Directive

The Payment Services Directive (PSD2) is European legislation that aims to open up the payments and financial sector to more competition.

We have covered this in 3 separate blog posts in terms of the security implications:

It would be repetitious to cover that material again, suffice to say the legal framework around handling payments has factored in a set of security controls that have regulatory force behind them.

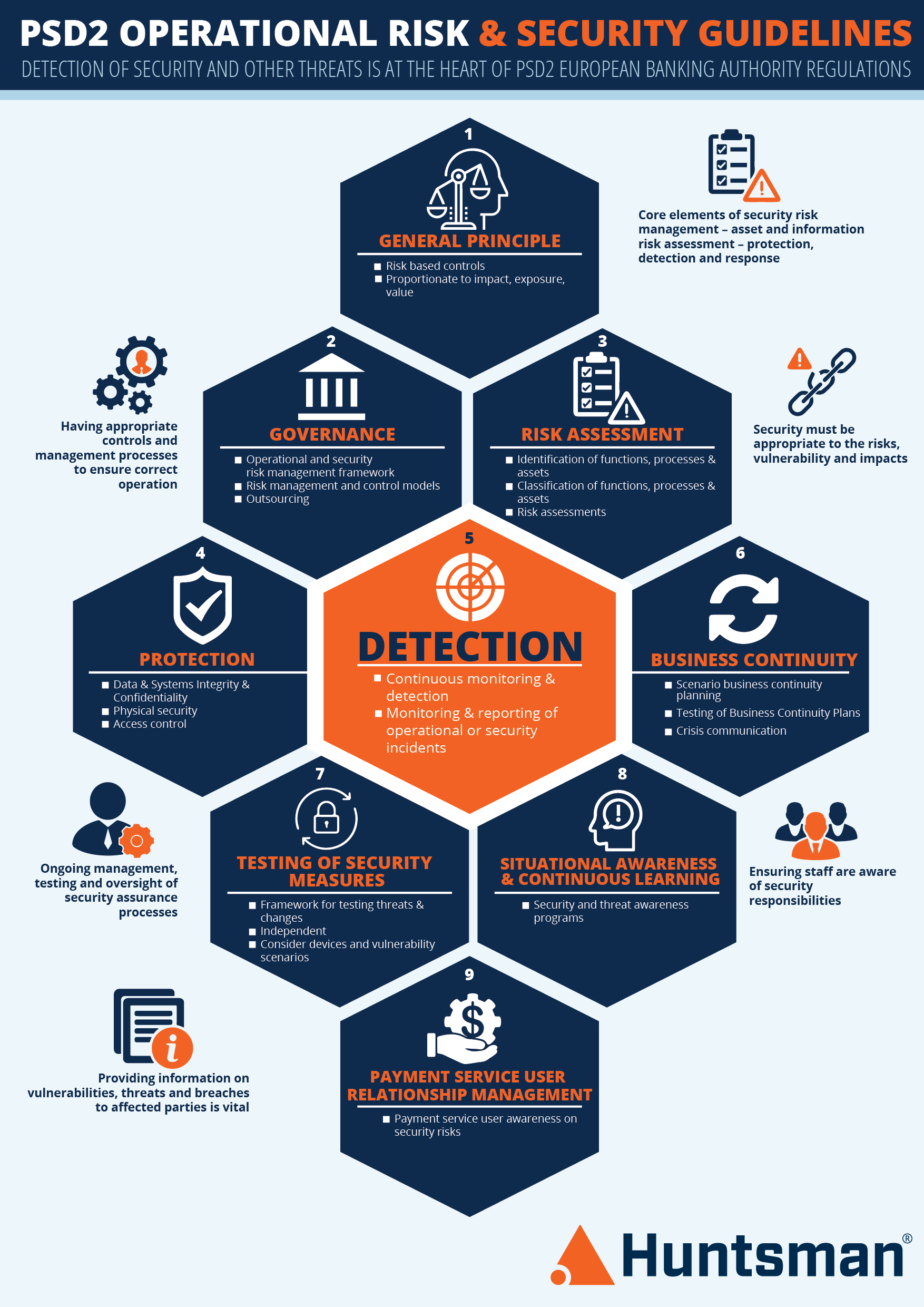

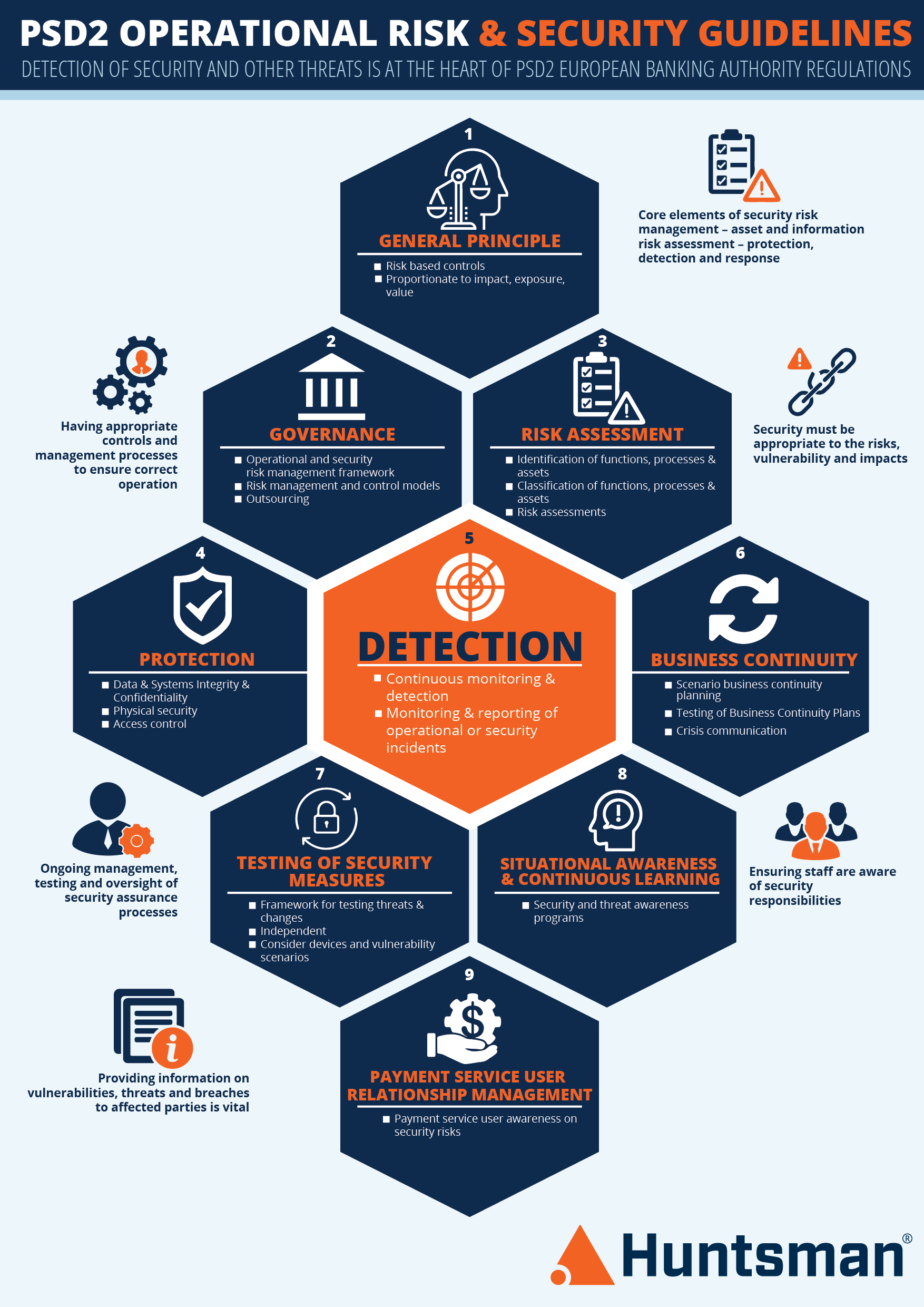

The Operational & Security Risk guidelines cover a reasonably familiar set of domains or subject areas. Nine in this case:

- General principle

- Governance

- Risk assessment

- Protection

- Detection

- Business continuity

- Testing of security measures

- Situational awareness and continuous learning

- Payment service user relationship management

See our infographic here.

NISD – The National Infrastructure Security Directive

The National Infrastructure Security Directive is defined at EU level, but being a directive, must then be transcribed into local laws and regulations.

It is designed to bolster cyber security and resilience within the critical infrastructure sector (so called “essential services” but also “digital services”). As such it’s broadly parallel to the C2M2 standard that the US has published.

In the UK (each country may have a different approach) there is no single oversight body – instead, a number of separate regulatory organisations (Ofcom, Ofwat, Ofgas etc.) are assisted by NCSC and the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

This diversity in the definition of rules, standards and processes to police compliance is a challenge. NCSC have published a set of high-level guidance objectives, or Indicators of Good Practice, for Critical Infrastructure organisations that cover:

- Managing security risk

- Protecting against cyber attack

- Detecting cyber security events

- Minimising the impact of cyber security incidents

The Huntsman Security Critical InfrastructureIndustry page and NISD Compliance page has more details, or see the NCSC guidance page itself at: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/guidance/nis-directive-top-level-objectives

Breach notification laws

The US has had data breach notification requirements for some time, at state level. Leaving the EU GDPR for now, the wider international picture has also been defining breach notification legislation to govern the process of handling and communicating breaches. By way of example:

- South Korea and Taiwan impose legal obligations for breach notification.

- Japan only requires notification in specific circumstances at present, but has recently been looking to tighten up its legal framework.

- Australia introduced mandatory breach notification laws (see this blog post) in early 2018, after many years of a more relaxed enforcement approach. These are still “bedding in” and have not yet had the same impact as American and European laws.

- Singapore is considering mandatory breach notification laws to augment its existing data protection regulations.

GDPR – EU General Data Protection Regulations

GDPR has been written about, blogged about, used for marketing and talked about at some length.

The way privacy is handled and the use of data is highly significant; as is the introduction of mandatory breach reporting laws for organisations that suffer losses.

The need for effective security, the protection of data from insider misuse and external attack; and the need for rapid detection and response to threats is deeply embedded in this regulation and so the next major EU security breach will be interesting – happening as it will under this new legal and enforcement regime.

We have written several blogs on this topic, which you can find here.

About Huntsman

About Huntsman